|

From the Beatus de Osma, 11th-century illumination of Revelation 7:9, via Wikimedia Commons November 1, 2017

The origin of this day began very early in the Church’s life in Ireland. As a day fixed on the Christian liturgical calendar, All Saints Day did not appear until the early 9th century in Rome. Although there are many layers of meaning that have been assigned over the centuries to the celebration of this day, at its root is a desire to express the intercommunion of the living and the dead in the Body of Christ. I would suggest, however, that it is even more primal than that. I wonder if a day like All Saints is also expressing a human longing to know that what we see is not all that there is. During my visit to the Galapagos Islands a few years ago we were traveling to one of the islands by speedboat, when about a dozen or so dolphins came up by our side and swam next to us, occasionally leaping completely out of the water. It was enthrallingly beautiful as we watched those amazing creatures. A young German woman in her early 30’s sitting next to me said out of the blue, “Do you think they have souls?” During a parish visitation where the parishioners placed written questions for me in a bowl, I pulled out the question, “Do you believe our dogs and cats have souls and go to heaven to be with us?” Another asked, “What do you make of the books giving accounts of people who have died and come back to life describing moments of profound light and even encounters with Jesus?” Such questions point to a hopefulness that there is indeed something beyond this life. As I discovered in conversation, the woman asking the question about the dolphins was a non-churched veterinarian, but she posed a spiritual question not knowing anything of my life’s vocation. Perhaps questions just like these are ones we need to be considering as we look to how to be the Church in this time of the 21st century. It is not the question itself that is most significant. It is the matter of the heart to which the question is pointing – the assurance that this life is not all that there is. All Saints Day celebrates that hope and assurance as we hear those great words from the Revelation to John: “After this I looked, and there was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages, standing before the throne and before the Lamb, robed in white, with palm branches in their hands.” All creation, what has been, what is and what yet will be, is held in God’s love. To this we are called to give witness. Bishop Skip Proper 25; October 29, 2017

Today’s Gospel brings us to another in a series of tests of Jesus. We heard one last week when Jesus was asked by the Pharisees whether it was okay to pay taxes to Caesar or not. This test appears to be relatively straightforward: “Teacher, which commandment in the law is the greatest?” Yet Jesus does an amazing thing in his answer. He uses the tradition, a response from Deuteronomy about loving God and a response from Leviticus regarding the love of neighbor, and marries them. Now loving God and loving neighbor become inseparable. No longer can one love God in private. To be in right relationship to God we must also be in right relationship to our neighbor. Let’s now back up a bit and look more closely at what is at play here. When the Pharisees ask this question of Jesus, they and Jesus know well that over time 613 different commandments had been enumerated in the tradition. They were not equally weighty, however. Each rabbi had his own way of ordering the precepts of the Torah, thereby reflecting his personal theology. If I were to ask each of you, “What do you believe is the purpose of your life in Jesus,” your answer would reflect something of your personal theology, your way of approaching God and faithfulness. The same thing is operative here. So when Jesus responds to the query with Dt. 6:5: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind,” and then says it is the greatest and the second from Leviticus is like it, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself,” it reflects his personal religious bias. He is saying also that the other 611 all hang on these two! What do these two commandments, apparently the center of Jesus’ own theology, tell us? First, love God. This is not merely a feeling or about affection, although it might include that. This is primarily about our will and what we are willing to act upon. This is about our life and how we order it. To love with all our heart, mind and soul means to do so with all of who we are: time, intentions, finances, business, vestry, family and anything else you can think of. The community of faith, what we call the Church, exists primarily to prepare the ground for worship and create an environment for holiness in the ordering of our life. The implications for the Pharisees in Jesus’ answer are that they are not merely to study the Torah, but they are to become the Torah. For us, we are not merely to study the Bible, but become the Bible. We are not just to come to worship, but become a worshipful being. We are not to only partake in bread and wine, but become Eucharist, the Body and Blood of Christ for the sake of the world. To love God with all of who I am is to live and breathe God, think God, be immersed in God. So if I am making a business decision, I am thinking about who I am as a person of God. If I am pondering marriage or any significant relationship, I ask myself how it honors God. How does the ordering of my house, my family, my finances, my leisure time, my care of the earth, reveal the love of God and my neighbor? Huge questions, yes? Being faithful, as Jesus sees it, is first about God, not me. Then he takes another step. The practice of our faith is not about me, but about we. Worship is most authentic by gathering as a community. Notice in our Prayer Book tradition that the words are continually we and us, not I and me. Furthermore, we cannot celebrate the Eucharist with our eyes closed to the needs of the world. The Orthodox tradition has a wonderful turn of phrase: “The liturgy of the Liturgy.” It means that worship must flow from this altar to the altar of the world. A story told by two American church workers in East Jerusalem may help underline Jesus’ point. A large number of Palestinians were gathered at a bus station across from the Damascus Gate. As you are aware this can be a place of great tension between Palestinians and Israelis. A group of young Palestinians began to taunt some of the Israeli soldiers when suddenly, a Palestinian father, carrying a small child in his arms, walked up to an Israeli soldier and shook his hand. As tensions eased, the relieved soldiers took out a pot of tea and shared it with the crowd. For you and me, our engagement with the world is like that cup of tea. This altar of our worship and communion with Christ and one another here at St. Stephen’s goes with us out those doors and everything we do. For a Christian every boardroom table is an altar, every kitchen table is an altar, every vestry meeting table is an altar. Loving one’s neighbor as oneself is more than a passing definition for Jesus. It is a radical way of living. Our allegiance, (hold on here!), is not first to self, country, work, money, the American dream, or Wall Street. Our first allegiance is the love of God and the love of sisters and brothers who are found everywhere and anywhere, all made in the image of God. We come again now to Eucharist, to be formed and transformed more and more to be the Body of Christ in the world. We are to become what we eat and drink. Leave worship today to greet the Christ already at work in the world. Loving God and loving neighbor, we pursue justice and peace for the entire creation. Bishop Skip St. Simon and St. Jude with St. Margaret of Antioch, detail of c.1410 tapestry, via Wikimedia Commons. St. Simon and St. Jude, Apostles

“On the foundation stones of the heavenly Jerusalem are written the names of the twelve apostles of the Lamb; and the Lamb himself is the lamp of the city.” (the antiphon for the Benedictus assigned for the day) Of Simon and Jude, two of the twelve, little is known. They tend to be linked because tradition places them as apostles to Persia, modern day Iran. Yet the antiphon above names them along with the other apostles as foundation stones of the heavenly Jerusalem. In Scripture we have glimpses of the conversations that took place among the original disciples. They include words of excitement, hope, disappointment, disagreement and even bickering. Sometimes they are clueless and other times great words of faith shine forth. Very human power struggles cause conflict and division. In the midst of it all, however, comes a vast reservoir of faithfulness of which you and I are the inheritors. Foundation stones indeed. Such grace, more often than not, comes to us from the little known saints whose paths we cross. They are also a part of our foundation. I am a person of faith in Christ Jesus today because of the original twelve, because of Simon’s and Jude’s “ardent devotion.” I am also a person of faith because of a third grade Sunday School teacher who with a twinkle in his eye taught me the awesomeness of God; an eleventh grade trigonometry/analytic geometry teacher who invited me to see the complexity of God and to trust my own giftedness; an elderly parishioner who helped me to revel in and enjoy the beauty of God as she danced her prayer. The list goes on. Who are these little known folks in your life? Who are the ones who have passed on the great repository of faith to you? Give thanks for them this day even as we bless God for the gifts of Simon and Jude. Bishop Skip Proper 24; October 22, 2017

We are witnesses today to an attempted set-up, the first of four controversies between Jesus and various community leaders. Some might even call it entrapment. You know what that is: The action of tricking someone into committing a crime in order to secure that person’s persecution. In the United States entrapment is illegal and people sometimes use it as a defense in court proceedings. Today we are looking at first century Palestine and whether illegal or immoral, the Pharisees are looking to entrap Jesus in order to bring about his persecution. They want to get rid of this prophet of God who keeps telling inconvenient truths that confront and even shatter the religious and political status quo. Jesus, a holy pest if ever there was one, keeps teaching through his parables and examples things like: all are welcome at God’s table; everyone is our neighbor; everyone has access to God’s grace and mercy; one’s station in life is not a measure of God’s love or one’s worthiness; the poor are blessed; the first are last and the last first. The list goes on. Such teachings are unacceptable to some, especially those who want certain groups of people subservient, devalued, or even dehumanized. A few representatives of the Pharisees greet Jesus with kind words, buttering him up if you will, in order to try and promote their real agenda. They call Jesus sincere, one who tells the truth, saying that he teaches the way of God and gives deference to no one. Compliments are filling the air, but they are empty words. Then they ask the million dollar question: Is it okay to pay taxes to Caesar or not? Jesus sees through the ruse, using the moment to teach something essential to his proclamation of the Kingdom of God if only they and we would have ears to listen. Jesus knows well that to encourage not paying the tax due to Caesar would be against the law. Thus like a good Rabbi he throws it back on them as he asks a rhetorical question to which the Pharisees know the answer: Whose image is on the coin? It is that of the emperor, Tiberius Caesar, minted and authorized by the Roman government. Furthermore, we know that the coin had inscribed on it these words: “Tiberius Caesar, son of the divine Augustus, great high priest.” Right on the coin itself is a claim to divinity for the emperor, at times even called son of god! A good Pharisee would see it as idolatrous, but nothing is sacred in this moment of attempting to ensnare Jesus in a conundrum. Although they are hoping to get Jesus to say something that will get him in trouble with the government, Jesus’ answer challenges them to have to deal with the very real question of whom they regard as Sovereign over all. Is it God, or is it the emperor? Who has the greater claim on their life, the Lord or the state, which by the way is a great question for us in 2017. The choice is left to the Pharisees just as it is left to us. In the Scriptures, to say that Jesus is Lord is also to say that Caesar is not. Preceding Jesus’ time in history, Isaiah too is very clear—“I am the Lord, and there is no other; besides me, there is no god.” The first two commandments of the ten are likewise clear that we are not to worship anything or anyone, but God alone. Idolatry is when we give something ultimate importance or a place of supremacy in our life that is due to God alone. Of course we do it all the time, which is why the Bible, in the story of Israel and beyond, warns us about it over and over and over again. Psalm 96 says, “…the Lord is to be revered above all gods…all the gods of the peoples are idols.” Let me offer you an example since the central image given us today is a coin – money. Again, Psalm 96 says, “Ascribe to the Lord honor and power. Bring offerings and come into his courts.” We do so at every liturgy, placing our offerings of bread, wine and financial treasure on the altar. If we look at the Scriptures, the thing Jesus talks most about is the Kingdom of God. What does he talk second most about? It is our treasure, that is, our money or resources. Why do you think that is so? It is because God knows that our treasure is God’s chief competitor. We make of it an idol, which is why when we put our treasure there our heart will be there also. Today's lesson from Jesus is not about the separation of church and state. That is a misreading. Today is teaching us that everything is God’s, including the emperor, including the coin, and if the Pharisees would pay attention to their own faith tradition they would know that as well as anyone. Our call is to treasure God for who God is, to treasure our relationship with God, and to nurture the ways in which we meet God in one another as we bear the image only God has bestowed upon us. The Christ in me meets and respects the Christ in you. The central way in which we are continually reminded who God is and who we are in relationship to God is when we gather in worship. The worship of God, through Christ, in the power of the Spirit, is the antidote to idolatry and the worship of false gods. So it is that we are gathered here today around this Table of the Lord. We do this to remember him partly because we so easily forget. Here we are re-oriented to the one God, living and true. The Pharisees were amazed by Jesus’ answer, yet left and went away. I wonder if we might be so amazed that we might instead be drawn closer to him and one another, as we gather to adore him here at Good Shepherd. Bishop Skip Detail of St. James the Brother of the Lord by Tzangarolas Stephanos, 1688, via Wikimedia Commons The Gospel of Matthew informs us that “A prophet is not without honor except in his own country and in his own house.” Ah yes, the old familiarity breeds contempt idea. People familiar with Jesus’ household fail to perceive God’s presence in him simply because they know his family origin and context. He is Joe and Mary’s boy. They know his brothers and sisters. His expressions of the truth of God are dismissed solely because of assumptions made about his family and cultural associations.

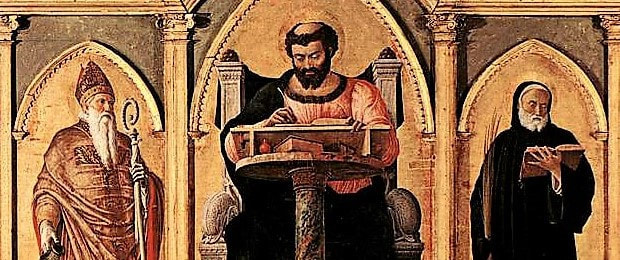

Have you ever felt judged because of being placed in a category whereby someone assumed he or she knew what your core values may be, or have you ever made superficial judgments of another person’s worldview simply because of ascriptions like liberal/conservative, Republican/Democrat, progressive/traditional, Black/Latino/White? The epidemic partisanship found in our cultural dialogues would seem to be calling for a greater familiarity with one another, that is, a willingness to walk with one another and truly get to know one another across perceived divisions. In the life of prayer, my experience is that familiarity fosters greater love. I find that more frequent participation in the Eucharist does not cause me to take it less seriously, but draws me into a deeper relationship with Christ, God’s love for me, and increases my desire to make a difference in the world for the sake of the Gospel. Familiarity can be empowering. The Semitic usage of the word brother can also mean cousin or other forms of kinship. I like the thought, however, that James was in fact Jesus’ brother. When James met with the Council of Jerusalem, as recorded in Acts 15, and supported the Gentiles who were turning to God by not imposing ritual restrictions, perhaps he had learned this understanding of God’s generosity and welcome to all from his brother. When James was placed on the pinnacle of the temple in Jerusalem and refused the direction of the authorities to turn the crowds away from Jesus, he was thrown down and cudgeled to death. He gave his life – for his brother and for the sake of unity. Who knows exactly what kind of relationship Jesus and James had, but they must have had a significant awareness of one other’s humanity. Accounts like this help keep us from emphasizing Jesus’ divinity at the expense of his humanity. James knew Jesus as only a brother could, and still came to faith after Jesus’ Resurrection. It also helps us remember that it is precisely through ordinary human beings, even those we call saints, that we see the grace of God working in glorious ways to shape the world and our attitudes toward one another. James was able to teach and act on the teachings of his brother. In this case, familiarity seems to have paved the way for greater intimacy between siblings, even love and respect. Maybe familiarity doesn’t always breed contempt, and honor can indeed come from one’s own house. Bishop Skip St. Luke shown in the San Luca Altarpiece (1453) by Andrea Mantegna, via Wikimedia Commons. October 18, 2017

The Gospel appointed for this day is Luke 4:14-21, where we discover an account of Jesus teaching in the synagogue. In Luke’s Gospel Jesus is called teacher thirteen times. With such prosaic underlining, Luke is emphasizing Jesus’ authority as he addresses people about God and God’s mission plan. Thus to follow the teaching that appears in this part of the Gospel, we learn that central to God’s mission is:

Interestingly, the text from Isaiah cited by Luke is not to be found on a scroll in that specific way, since it is an artistic weaving of two different passages from Isaiah. Luke is seeking to make a theological point. He omits the portions that might allow a spiritualizing of the text in order that we understand that it is precisely the economically, physically and socially unfortunate about whom he is speaking. One can never say, if we read the Bible accurately, that it does not involve politics. Mind you, not partisanship, but certainly politics. A faithful life will always have political implications of some kind. It was so for Jesus and therefore for us. Remember, it was a government that executed Jesus. You and I therefore are to participate with God in seeking to bring about the new creation God desires for all. The four points above are always a good reference point for any of us as we examine our personal life and how we might be co-creators with God in its building. They are also a good checklist for any vestry or even an entire diocese, an examen if you will, to see if the ministry we are about as a body contributes to the realization of Jesus’ teaching. There is no better beginning or ending in our mission to follow Christ. Bishop Skip Proper 23; October 15, 2017

Most of us like a good wedding reception. People tend to be happy, hopefulness is in the air and good friends and family are enjoying being with one another. In first century Palestine the wine would be flowing. Yet, just like with many weddings, something unexpected occurs. This event is no different and we get various odd twists and unexpected guests. One of the uncomfortable plot-lines is the note of judgment. Judgment as understood here is not condemnation, it is more like a wake-up call. All through this parable we have alarm clocks going off, events that are there to startle the hearer and bring about the possibility of seeing in a new way. This parable challenges us to wake up and understand that God is not about business as usual. As always, parables are offered to unsettle something in us, get us to take note and thereby make room for God. Note also that the parable is one of grace. Grace is something we find hard to believe or even sometimes allow. Do you remember the reactivity when the Amish community in Pennsylvania forgave the shooter of their children in the tragedy at their school? I am aware of some who are horrified that we pray for all in the massacre in Las Vegas, including the shooter. Doing so is hard, to be sure, but it is faithful. We are so very afraid that someone somewhere is going to get something she or he doesn’t deserve, especially if we know how hard we work and believe ourselves to be deserving. We may know in our heads the theology that “we are justified by God’s grace through faith,” but we often live as if we are justified by our own merit and what we contribute. Surely, we must have to dosomething! Listen to Frederick Buechner in his little yet grand book, Wishful Thinking: A Theological ABC: “Grace is something you can never get but only be given. There’s no way to earn it or deserve it or bring it about any more than you can deserve the taste of raspberries and cream or earn good looks or bring about your own birth. People are saved by grace. There’s nothing you have to do. There’s nothing you have to do. There’s nothing you have to do.” Our own catechism says it well: “Grace is God’s favor toward us, unearned and undeserved.” Scandalous. We come now to the first note of grace. God wants to celebrate. We have a God of the party and we are invited! It is a party in honor of his son, (think Jesus here!), and today this Eucharist is a party, a celebration, in honor of Jesus. But now the alarm goes off. Why? Those invited in a free act of kindness can’t bother to come! So a second invitation goes out. The dishes are ready and hot—there’s a sense of urgency, but he invitation is made light of as they have things to tend to at the farm or business. They made excuses. We make excuses. God hears more excuses than a State Trooper. The world, then and now, is full of folks who don’t know a good thing when it is right in front of us. Free grace, dying love, extravagant acceptance – it’s all absurd. It’s too good to be true. I wonder. What are we running from? The best thing ever offered is God’s banquet where all, no exceptions, are invited to the table. Maybe it’s because some part of us doesn’t really want to be transformed and set free. It’s scary to trust such all-encompassing boundless love. So we cling to our insular worlds, stick to what we think we already know, self-justify and believe that if we’re just kind to others and behave ourselves we’ll get to the party. The danger of course is that we turn Christian life and faith into a minimalist moralism that never transforms anyone. Here’s the kicker. God still invites, still pursues, as the second alarm clock goes off and the invitation is offered to those on the streets – the societally outcast and despised. Apparently, God doesn’t play by the rules! The hall is then filled with guests who have come for God-knows what reason, including those who would not be on our list of the deserving. Think here any person we would prefer not to see at our own dining room table, even as God invites them to his banquet table. This is the part of the parable that is supposed to offend our good sensibilities of societal categories. The message is this – one is saved, that is included in the banquet, by accepting the invitation, no matter who you are or what your life history has been. Now we come upon one more wake-up call. The guy without the wedding robe appears. Very odd. We have to presume that others were given one to wear, nevertheless, here he is attending the party. The king wonders how he got in and he is kicked out, but note – no one is kicked out who wasn’t first in. God’s grace tells us that the invitation is our way to God’s party, not our track record. Yet the truth is that we are given free will and we can, if we want, refuse the gift of the robe of acceptance and turn down the invitation. God doesn’t force us to show up and we get the point that for a follower of Jesus, complacency is not an option. St. Augustine has said that we are to “love God and do anything we want.” His point is that in loving God, everything we do will be shaped by that love. The way we live life then becomes an act of thanksgiving for the grace given, not a way to earn God’s acceptance of us. Our responsibility as the Church is to do all we can to make God’s banquet available to anyone and everyone just as it is for us. Take a seat. Let us keep the feast. Proper 22: October 8, 2017

(A continuing commentary on last week’s Gospel in response to Jesus’ argument) This is a story of a long-time resident in a European village. He was known to all as one who was always kind, was a favorite of the children, and would do anything for anyone in making himself available to any person’s need. On the day of his death plans were made for his burial. As it turns out, he did not share the same faith as most of the townspeople and therefore it was prohibited for him to be buried in the town cemetery. This was upsetting to many, but the religious authorities had to uphold the established rules. So the interment occurred and the man was buried just outside the fence that marked the boundaries of the cemetery. A strange thing happened late that night, however. For when people awoke the next day, it was discovered that someone had gone to the cemetery and moved the fence to include the grave of the kind-hearted village man who had been buried the day before. Enter, stage right, the chief priests and elders of last week and today’s Gospel, the religious and civil leaders of their day. They were so caught up in themselves and their own sense of righteousness, they could not imagine God’s great desire for all the inhabitants of the vineyard as Isaiah put it: to “sing for my beloved my love-song.” Once again, the Gospel, as Jesus presents it to us, turns things upside down. You know: the exalted are humbled and the humble exalted; the last shall be first and the first last; the rich will be sent away empty and the poor will be given good things; the mighty are cast down and the lowly are lifted up. We don’t always do real well with that. We live in a culture that too often exalts the exalted and believes the first ought to be first and the last deserve to be so. Do you see what is going on in this account in Matthew’s Gospel? As we saw last week, Jesus engages the chief priests and elders who are wondering where he gets his authority, all by the way so that they can discount anything he says. Then follows three parables – the one of the two sons last week and then today two more parables, those of the vineyard and the wicked tenants. Each of these three parables is a commentary on the dispute Jesus is having with the authorities and is addressed to them. Amazingly, the chief priests and elders are pronounced guilty, for they have in the first parable today rejected the prophets, those whom God had chosen to be God’s truth-tellers. By throwing them out of the vineyard as the parable account goes, the religious and civil authorities have become the so-called wicked tenants of today’s second parable as their hearts have become closed to God’s call. That’s how people end up being buried outside the cemetery fence. The beautiful, welcoming, extravagant love-song of God that is meant for everyone is what gets Jesus in trouble. He is always moving the fence so that everyone is included, especially the ones often not immediately obvious to us. It sets up the conflict between Jesus and the Jerusalem leaders, eventually leading to his excruciating death. The fear of the chief priest and elders, and sometimes ours, is that someone just might get something they don’t deserve. But let me remind you of our catechism’s definition of grace: “Grace is God’s favor towards us, unearned and undeserved.” Garrison Keillor has said, “Every family needs a sinner to save us from self-righteousness.” Yet the Gospel goes much deeper than that. What makes the Gospel and the account we have last week and today such a revolutionary word is the upside down message Jesus is telling us about God. It is this: God’s mercy, God’s loving kindness, is not dependent on human virtue at all. It is based solely on God’s generosity, a love that comes from God who desires that every person is, regardless of personal history, invited to enter the glorious freedom of the liberty of life in him. It is true for the tax collectors and sinners, it is true for the tenants of the vineyard, it is even true for the self-righteous as they are called to receive the grace offered. In other words, it is true for us. The heart of the Gospel is the shocking paradox, yes shocking, that the last, the broken, the sinners, the least, unexpectedly enter the Kingdom first. It is a danger to think that we are self-sufficient because we are so good at pulling ourselves up by our bootstraps, to live at the top of the moral pile in order to look down at those beneath, or live off of the energy of contempt for others in the game of self-righteous one-upmanship. Our Baptism and Confirmation into Christ calls us to name all of that as the trap and lie that it is. It destroys community. Today’s Gospel is about knowing our need of God and the “surpassing value of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord.” If we see ourselves as we really are – children of God who know brokenness and grace, honesty and deception, not all good, not all bad, we can admit that merit on our own is not enough. Yet we know with certainty that it is God who is enough for us all, for “Christ Jesus has made you his own.” All is gift. God sings the song of love for you. Bishop Skip The 17th Sunday after Pentecost, Proper 21

October 1, 2017 I had been driving out and about in the Diocese and got hungry, so I stopped to pick up a sandwich. Instead of sitting in the parking lot I drove over to a pullout near a park to eat before returning to the office. I remember a Vaughan Williams piece was playing on Sirius, Fantasia on Greensleeves, when a car pulled up next to me. I wasn’t paying close attention, but two people got out with a loaf of bread, and seemingly out of nowhere 30-40 seagulls appeared. Pieces of bread were being launched into the crowd as wings flapped wildly, with only bread on the mind. A cacophony ensued drowning out Vaughan Williams. The chaos was orderly as chaos goes when a funny thing happened. A duck, a lone male mallard appeared and dared to enter the assembly. As he made some rather feeble attempts to join the party it became apparent that he was not going to be tolerated. Three gulls set upon him and chased the duck out of the group, down through some trees until I lost sight of them. Neither the seagulls nor the duck returned to the frenzied feast still going on. Evidently, the seagulls were so fixed on themselves and their place in the pecking order (ahem), and getting rid of one unlike themselves, they missed out on their own source of food and the great party that was taking place. Enter, stage right, the chief priests and elders of today’s Gospel, the religious and civil leaders of their day. They, like the seagulls, were so caught up in themselves and their own sense of righteousness, they could not fathom the party of grace that God wanted to throw for the so-called tax collectors and sinners and indeed, wants to throw for the chief priests and elders as well! Once again, the Gospel, as Jesus presents it to us, turns things upside down. You know: the exalted are humbled and the humble exalted; the last shall be first and the first last; the rich will be sent away empty and the poor will be given good things; the mighty are cast down and the lowly are lifted up. We don’t always do real well with that. We live in a culture that too often exalts the exalted and believes the first ought to be first and the last deserve to be so. Do you see what is going on in this Gospel story? As Jesus engages the chief priests and elders who are wondering where he gets his authority, all by the way so that they can discount anything he says, he responds like a good rabbi and answers a question with a question. Jesus uses a very recent example in the life of Jerusalem and brings up his cousin, you remember, John the Baptist. They find themselves in a bit of a pickle as they cannot say what they really think about John the Baptist as he does not fit into their religious or civil categories. They’re stuck and so respond, “We don’t know.” Then follows the parable of the two sons that is a commentary on the dispute. Amazingly, the chief priests and elders are pronounced guilty for their hearts are not receptive to God’s call. Obedient faith is always the final test for Matthew, so when the tax collectors and sinners, last on the list for God’s welcome on most people’s list are thrown a party of grace, it cannot be tolerated. This wild, welcoming, extravagant party of grace that is meant for everyone is what gets Jesus in trouble. It sets up the conflict between Jesus and the Jerusalem leaders, eventually leading to his excruciating death. The fear of the chief priest and elders, and sometimes ours, is that someone just might get something they don’t deserve. The problem is not that the chief priests and elders or even the one son who did not do what he said he would do are bad people, or on the flip side, that the tax collectors and sinners and the son who first refused and then came around are such good people. The problem occurs when some wish to celebrate their own sense of righteousness as better than another’s, and thus have no need to repent – to walk in a new direction. And in this case, the tax collectors and sinners as well as the son who eventually came around knew of their need. Garrison Keillor has said, “Every family needs a sinner to save us from self-righteousness.” Yet the Gospel goes much deeper than that. What makes the Gospel and the account we have today such a revolutionary word is the upside down message Jesus is telling us about God. It is this: God’s mercy, God’s loving kindness, is not dependent on human virtue at all. It is not based on moral rectitude, that is, getting it all right, or even moral turpitude, getting it all wrong. It is based solely on God’s generosity, a love that comes from God who desires that every person, regardless of personal history, is invited to enter the glorious freedom of the liberty of life in him. It is true for the tax collectors and sinners, for the son who finally came around, it is even true for the self-righteous as they are called to welcome the grace offered. In other words, it is true for us. The heart of the Gospel is the shocking paradox, yes shocking, that the last, the broken, the sinners, the least, enter the Kingdom first. It is a danger to think that we are self-sufficient because we are so good at pulling ourselves up by our bootstraps, to live at the top of the moral pile in order to look down at those beneath, or live off of the energy of contempt for others in the game of self-righteous one-upmanship. Our Baptism and Confirmation into Christ calls us to name the above as the trap and lie that it is. It destroys community. Today’s Gospel is about knowing our need of God. If we see ourselves as we really are – children of God who know brokenness and grace, honesty and deception, not all good, not all bad, we can admit that merit on our own is not enough. Yet we know with certainty that it is God who is enough for us all. This is the promise of Jesus. All is gift. Welcome to the party of grace. Bishop Skip Dear People of God of The Episcopal Church in South Carolina,

A pall of darkness and horror has once again fallen over our beloved country. In the massacre in Las Vegas we know as of this writing that 58 people have died and more than 500 have been injured. It was an unspeakable act of evil. Our hearts go out to all the victimized, including their families, as we hold them in prayer that somehow mercy and grace may be known to them. Many times this comes in the form of the first responders, pastors and medical personnel who tend to their needs. They need our prayer as well. The Episcopal Bishop of Nevada, Dan Edwards, and the people of the Episcopal Church there, will be right in the middle of the responses needed so that a word of love may be spoken in the midst of hatred and violence. Bishop Edwards has asked that the Episcopal Churches across Nevada toll their bells in mourning at 9:00 a.m. Pacific time tomorrow, once each time for the number of those killed, including the perpetrator. I am asking that our churches in South Carolina who have bells to toll them at 12:00 noon Eastern time onTuesday, October 3, to join in solidarity with our sisters and brothers in Nevada. In addition to our prayer, we must also act. We must find a way to be in conversation about the culture of violence sweeping our nation and engage in repentance for whatever ways we participate in that culture, even unwittingly. The nature of gun violence in particular, as we know, is wrapped up in issues of poverty, class, mental illness and race. A serious conversation leading us to enact reasonable gun laws must be had and so far it has eluded us as a nation. Some of you are aware that I am one of the Episcopal bishops who join in a group called Bishops United Against Gun Violence (BUAGV), and I direct you to that website for information: bishopsagainstgunviolence.org. We ask hard but necessary questions such as: "Why, as early as this very week, is Congress likely to pass a bill making it easier to buy silencers, a piece of equipment that makes it more difficult for law enforcement officials to detect gunfire as shootings are unfolding?” “Why are assault weapons so easily available to civilian hands?" Our goal must not be just better laws, however. We are about changing hearts and human transformation. We follow the Prince of Peace and name Jesus as Lord. We are about healing and wholeness, building bridges across lines of division and hostility. This is the work we must continue to do, work that participates with our prayer and longing for the healing of the nations. Please join in the ringing of bells tomorrow as you are able. Do gather together in prayer wherever you may be at that time. I leave you with the familiar, but oh so beautiful, A Prayer Attributed to St. Francis: Lord, make us instruments of your peace. Where there is hatred, let us sow love; where there is injury, pardon; where there is discord, union; where there is doubt, faith; where there is despair, hope; where there is darkness, light; where there is sadness, joy. Grant that we may not so much seek to be consoled as to console; to be understood as to understand; to be loved as to love. For it is in giving that we receive; it is in pardoning that we are pardoned; and it is in dying that we are born to eternal life. Amen. (Book of Common Prayer, page 833.) Blessings, peace and love to you all, Bishop Skip (I am grateful to my sisters and brothers in Bishops United Against Gun Violence for the Inspiration for this letter.) |

Bishop Skip AdamsThe Right Reverend Gladstone B. Adams III was elected and invested as our Bishop on September 10, 2016. Read more about him here. Archives

December 2019

Categories |

Copyright © 2024 The Diocese of South Carolina

P.O. Box 20485, Charleston, SC 29413 - 843.259.2016 - [email protected]

P.O. Box 20485, Charleston, SC 29413 - 843.259.2016 - [email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed